Suddenly, it failed

It happened at the beginning of 2017. Our number of clients had grown steadily so far, and we were confident our current MQTT clusters configuration was strong enough to cope with it for a while.

Wrong! So wrong! While we were quietly preparing for weekend leave, several alarm bells rang: rabbitmq node 1 not responding, then another, finally the entire cluster. Ok, no worries, let’s just restart it. Wrong again! While it’s easy to change a tire on a stopped car, doing it when you’re driving at 200 km/h is another thing: clients trying to automatically reconnect were preventing a smooth restart. After several unsuccessful attempts, lot of sweat, and placing the cluster in a safe mode, we finally managed to get it back to work.

After the storm, time to look back

With this painful event, we realized we were still operating our message brokers, and everything around, as if they were handling a few hundreds of clients. Although we knew we would have to strengthen this core part of our infrastructure, it wasn’t showing any sign of weakness. The danger of things working well is you quickly forget them! And in a small but rapidly growing shop like ours, priorities change. Still, reality strikes back to make you face all the things you are missing:

- strong isolation: a single message brokers cluster that does everything (internal/external communication) is very convenient at the beginning: it’s cheap and easy to setup. But one piece failing and the entire system is out. Also, upgrading or simply tuning becomes a stressful operation.

- performance tests: what are our needs if number of clients double? Are we able to deal with forecasted throughput? What happens under flaky network conditions? What harwdware for that?

- clear disaster recovery procedures: a document with some basic steps isn’t enough. Let’s learn from disasters, and shape up a correct recovery plan with realistic scenarios and steps.

This article focuses on 1st point (but we worked also on the others, performance tests were one of the prerequisites for developing the solution).

Divide and conquer

We expose our services through different APIs and protocols, but most of the activity comes from asynchronous messages processing that come from various sources: internal (microservices communication based on AMQP) and external (MQTT and STOMP, available for mobile apps, web apps, devices).

As a matter of fact, if something goes wrong with the broker, all communications stop. And things can go wrong in a lot of ways: broker crash (not so often), massive reconnection event (thousands of devices reconnecting at the same time), or sudden spike of messages in a specific exchange (if consumers aren’t fast enough, messages will pile up and performance can degrade for all the system).

Also, brokers exposing different protocols to various types of clients need to play with a lot of constraints: you need to tune for both throughput and high number of connections and you’re over-exposed to bugs due to the large number of plugins and custom settings you have to put in the game.

Finally, if you open communication channels to partners or external developers, you can’t easily isolate environments (privisioning, security, compliance, …) and probability of occurrence of a problem increases dramatically (for instance with bugs from incorrectly coded firmware), and you’re rapidly stuck with inextricable compatibility or upgrade issues (like impossibility to server different protocol versions to different clients).

Taking into account the experience we grew with RabbitMQ, and the large set of topologies you can build with it, it was a valid choice for us to help us build our next messaging system.

Splitting brokers

The plan was then to split the broker (actually cluster of brokers but we’re refering to it as a single entity). The plan was to create a backend cluster to keep backend communications completely internal and expose external channels through gateway brokers that could be located in different places of the world. But those brokers would have to send messages to each others (between backend and each gateway, not between gateways).

To do that, RabbitMQ has 2 plugins called federation and shovel. Deciding which one to pick depends on target topology, patterns of message transfer and level of control you need.

We rolled out the plan in several phases, but are the 2 major steps:

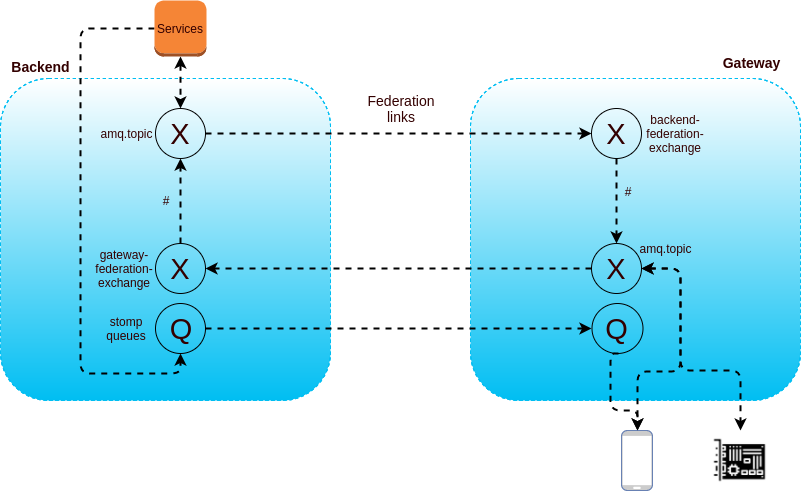

- 1 backend cluster + 1 gateway cluster with direct messages routing through federation. Below a logical representation of how they communicate:

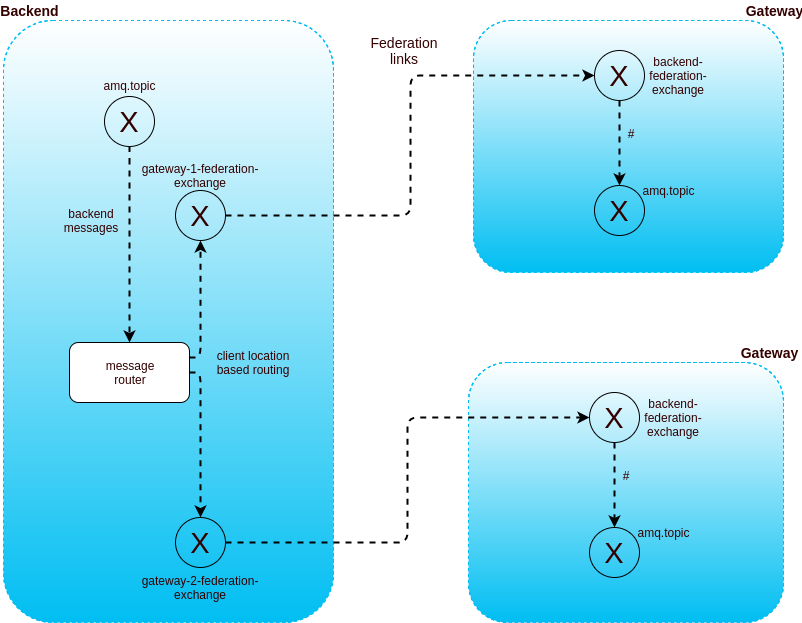

- 1 backend cluster + X gateway clusters with intelligent routing: when messages need to be routed to more than 1 gateway, it becomes inefficient to send all messages to all gateways. We developped a simple message router that route messages based on known location of the client (and broadcasts in case of doubt).

Clients are routed using AWS Route53 latency-based configuration.

Tuning RabbitMQ

It’s possible to tune RabbitMQ for throughput or for large number of connections. This is well documented here. We naturally applied those recommendations in order to maximize throughput on the backend cluster, and increase capacity to handle large number of connections on gateways.

We have also enabled HiPE compilation to increase throughput on some clusters and this is giving excellent results.

Running on AWS, we chose the ‘c’ type for our instances: RabbitMQ can be CPU intensive, for throughput intensive workloads, or when connections churn is high (which happens quite often if you have clients connecting from everywhere). We favored c3 instances (cheaper storage with SSD instance store volumes – requires snapshots for instance crash recovery) but c4 with proper IOPS configuration (gp2 or io1) does the trick (more expansive but data survives server crash or restart).

Repeatability

The way we decide to deploy and locate gateways is data-driven: we do it depending on current number of customers per region/country, forecast in sells, new projects, and technical factors. Once we are aware of those parameters, it’s important to make the operation of setting up a new gateway as automatic as possible.

Of course, spinning up a new gateway isn’t just a matter of 1 new server in an AWS region: we have to setup the VPC, VPN connection with backend, proxy servers, and other IT support instances.

We did it using Hashicorp Terraform: it lets you declare and interact with AWS resources from declaration in simple configuration files. Almost all AWS resources are available, see here.

Now if need to spawn a new gateway, it’s a matter of hours.

Where we are now

We started deploying these solutions in productions in March, and now we have 2 gateways in production (US and Japan), handling tens of thousands of connections.

Scalability and resiliency improved, and we significantly reduced number of problems we used to have. Also, massive reconnections are much less massive, by design: fewer clients per node, and clients are geographically closer to brokers, which reduces risk of network hicups.

We also improved maintainability: upgrades are progressively applied accross clusters, and we aren’t tied to a single solution anymore: if we decide to go for another messaging implementation for a particular need, it will be much easier to plug in.

Next steps

We want to achieve strong high availability, using AWS Route53 latency + health checks based routing. This will answer the question “what happens if the entire cluster of brokers is down?”. A good example can be found here

Split, split again! Internal workloads handled by the core cluster can be further segragated, by sending messages to dedicated message brokers, where relevant. Specifically, some of our workloads are log-oriented, don’t need true real-time processing, and would benefit from several days of data retention. Using something like kafka or kinesis would help in that matter.