We’ve been using Apache Spark for 1 year, and we wanted to share some thoughts and tips about it.

Spark is beautiful. It has a strong and simple API, a vibrant community, a wide ecosystem and lot of satellite projects. However, it doesn’t come for free: you need to understand its API, internal structures, and deployment methodologies. Setting up a cluster, maintaining, designing applications and jobs, … All of this can be overwhelming and looks like a daunting task at first.

The goal of this article is to provide overview, instructions and tips on how to build, deploy and maintain a distributed data analytics application based on Spark, with a particular focus on Spark Streaming.

Context

We decided to go for Spark at EnergyWise firstly to ingest and analyze streams of sensors data. We design, build and sell air quality monitoring products, that are used to monitor and trigger actions based on air quality measurements.

We had several options on the table (AWS Kinesis, Apache Storm, …) but we decided to pick Spark for the following reasons:

- unified platform for data streaming and batch analysis (lambda architecture), with machine learning capabilities

- heterogeneous team with different background and technical skills

- tight budget

As of now, some other options may be available to you, like AWS Kinesis Firehose.

We started with Spark 1.2.0 in test, and went in production with 1.3.0 few months later.

Our first Spark job was a streaming job, one to clean and store sensor data sent by devices. It made us discover Spark architecture, application deployment process, and fault tolerance semantics.

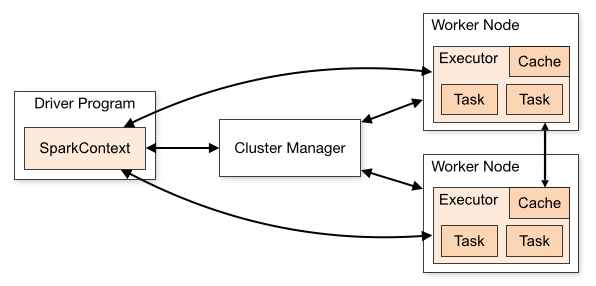

Spark cluster topology

I won’t go into details here as it has been extensively described in main Spark documentation

Here is just a quick reminder of main Spark processes

- Master: this is the main process responsible for coordinating cluster, scheduling jobs, restarting failed workers, …

- Worker: a worker node is where executors can be launched.

- Executor: started by workers for a given application. There may be 1 or thousands of them, depending on task configuration. They execute the application and store data in memory or in persistent stores.

- Driver: application submitted to the cluster that contains the main() method.

There are 3 deployment methods if you want to run your own cluster:

- Standalone (comes with AWS EC2 deployment scripts)

- Mesos

- YARN

And there are several companies that sell Spark cluster management, like Databricks (created by creators of Apache Spark), Hortonworks, Cloudera, and even AWS and Google are proposing services.

Here comes the first question you may be asking yourself: will I invest in my own Spark clusters (probably several if you have test environments), or can I use an hosted and managed cluster?

Own cluster VS Managed cluster

Having your own cluster will let choose your configuration, that may not be easy with a provider. For instance, Databricks doesn’t let you choose your AWS instance type (it’s a r3.2xlarge and that’s it!).

Another important point is that, especially in the case of clusters dedicated to batches, or even with streaming applications that run on over-sized clusters where there is CPU and RAM available, you could share instances for other tasks. Mesos and YARN let you share resources between clusters, so you can efficiently allocate resources and avoid wasting money.

But there are also advantages using an hosted solution: you don’t need to know a lot about Spark or system administration before you start your first data exploration job. Not all teams have someone available to setup (and maintain) a cluster, and Spark is all about giving instant access to big data analysis. In that perspective, a managed cluster is a good solution.

It can also be interesting if you want to temporarily create a cluster: Spark version upgrade testing, scheduled jobs, external users access to your data and jobs, …

Last but not least: you don’t need a cluster to start testing Spark! You will see it when you start reading Spark programming guide, Spark can run on your own machine, just pick a reduced dataset and don’t try to load terabytes of data.

That’s one of the main strengths of Spark, you can develop and test your whole job locally.

Deploying Spark on AWS EC2

Say you decide to give a try to Spark with your own standalone cluster, on AWS. Spark comes with a set of scripts that let you deploy a cluster from a command line. Documentation is available here. You can deploy inside or outside of a VPC, define your spot instance price, or choose your instance types for both master and workers.

Speaking of master and workers, there is a first budget optimization you can do here: you can share the master node, that will rather go unoccupied with only the master process and your driver. You can start one or more workers on it.

Spark EC2 will also do several other things:

- create 2 Hadoop clusters, one said ephemeral because it’s started on SSD instance storage, another said persistent (not started by default). It allows you to store and fetch data on HDFS, and it’s also used by Spark internals and application checkpointing.

- create a Tachyon cluster for in memory caching

- add monitoring agents with Ganglia

When your cluster is built, there are 2 web UIs available where you can monitor Spark and your instances:

http://<spark_master>:8080/is the Spark Web interface. There you can check health of master, workers, executors and jobs.http://<spark_master>:5080/ganglia/is the Ganglia master UI (monitoring of hardware, processes, memory, …).

Cluster management

Your cluster is up and running, you may now wonder what you will have to do to keep it healthy. There are some things you need to automate to ensure nothing breaks without you being alerted, and also to simplify provisioning (adding and retiring nodes).

Adding nodes

Spark EC2 scripts doesn’t help on this (hey, they already did a lot!). The way we do it at EnergyWise is based on AWS AMIs: we build an AMI from one of the worker nodes freshly created and configured.

The first thing is to let your master node know about this new node: you have to edit spark configuration (slaves files under spark and spark-ec2) and hadoop configuration (slaves under ephemeral-hdfs) to add the host name of your newly created instance. Don’t forget to r-sync all these files (spark-ec2/copy-dir command).

When you launch a new instance from this AMI, there are processed that must started so your node is operational:

- start Hadoop data node:

sudo /root/ephemeral-hdfs/bin/start-dfs.sh - start Ganglia agent:

sudo /usr/sbin/gmond - start Spark worker:

nohup sudo /root/spark/bin/spark-class org.apache.spark.deploy.worker.Worker spark://:7077 &</code>

Note: if you use Tachyon, above steps apply too.

Scheduling clean up

Jobs are started on worker nodes and will produce logs in $SPARK_HOME/work/. Each application jar version will also be stored on each worker running it. If you run a lot of them, disk space will decrease.

Below are cleanup tasks that can be scheduled with cron on each worker node and that removes logs and jars after 30 days. Warning: this assumes you redeploy at least every 30 days!

find /root/spark/work/ -type f -name "std*" -mtime +30 -delete

find /root/spark/work/ -type f -name "*.jar" -mtime +30 -delete

Also, Spark AWS deployment comes with a Hadoop cluster that also needs maintenance. Hadoop logs cleanup task can be scheduled the same way:

find /mnt/ephemeral-hdfs/logs -name "hadoop*.log.201*" -type f -mtime +10 -delete

System failures handling

You may have started with 1 or 2 worker nodes, but you may end up with dozens of them. Eventually, one or more servers will fail. They will. You have to anticipate it: a streaming job may not stop too long!

Few tips to anticipate a failure, in case you chose standalone deployment mode (different approaches apply for Mesos or YARN):

- On AWS, create AMIs from both master and worker node types. We already talked about the latter, but it can help to have an image for the former. This way you can start a new master instance and restart your workers one by one to point to the master

- Spark deployment guide already covers this: have a standby master

- You could also study the creation of a standby cluster: one that is an exact replica of the running one, but that you let shut down (so you save the price of running instances, but not EBS volumes unfortunately). It can be created on a different AWS availability zone or region than the other one, in case the first may become unavailable for a moment. It can also be used for blue/green types of deployment.

Monitoring

Monitoring is essential and can’t be skipped. In our case, with streaming jobs that must run 24/7 in multiple data-centers, monitoring and alerting are vital.

Your first weapons are Spark and Ganglia UIs, which are very good at collecting monitoring information about instances. Spark UI will help you find failed jobs and stages, application exceptions (log files are accessible in Executors tab), receiver exceptions (Streaming tab).

You also need to be alerted when something goes wrong; that’s something we do with logstash (1 by cluster node) by analyzing jobs and workers log files for specific exceptions.

Spark master also comes with a REST API that you can query periodically to check health of each job.

In the particular case of a streaming application, you can also monitor:

- batch processing time: if it’s frequently above your configured batch interval, your job is too slow at processing received and records and lags behind. Another hint for that is an increasing number of waiting batches. You need to either increase batch interval, add cores/mem to your job, optimize it.

- input stream pending records: if you use a broker like Kafka or RabbitMQ, check that your job is able to process incoming events. Spark has flow control mechanisms to move pressure back to the sender, still you may want your data to be processed in a timely manner.

Spark application development

Good, you have your own cluster now! It’s time to run something on it. This part won’t cover the basics of how to write a streaming job with Spark Streaming API, but rather try to list some useful tips on application development and life-cycle management.

A very complete programming guide is available here and is a good start point. Working examples are available in Spark github repo

Cores are expensive

You’re still in the early stages but want to use Spark anyway. Spark streaming applications require at least 2 cores to run, and that can look overwhelming if you already think about the dozen of small streaming jobs you want to write.

A quick solution is to write a single driver with several output operations. You can then make different jobs share the same resources, within the same driver execution process. It’s still possible to scale, as it will benefit from adding additional cores to driver the same way a driver with a single output operation would do (you’ll have to define spark.streaming.concurrentJobs to parallelize processing of jobs in a single driver) . Another advantage is you can create much cheaper integration test environments.

The drawbacks are:

- you loose code and process isolation, and you’ll have to redeploy everything even when you want to upgrade a single job. Code your driver with future splits in mind.

- debugging can be much harder.

Stateful operators: think twice

They look apealing, and can do really great job. However, logic for stateful operations in a stream are more complex than other kinds, and more complex to debug.

First of all, a common mistake we made at the beginning (saw it also in different mailing lists conversations), is to use stateful operations as persistent stores. They are not, of course, and they are wiped out when checkpoint directory is cleared. You have to save everything that needs to be in a reliable persistent storage. Stateful operations are great to store transitive states that you can afford to lose or are easy to store and restore on startup.

Complexity in writing a working and maintainable job is also something to avoid. There are usually other ways to write the same job without using stateful operators (like persisting and fetching everything in DB)

Event-driven

Think event-driven: streaming applications will run micro batches every few seconds. Is it ok to fetch static or live data from your relational database everytime, for every received record? It is a possible solution, but it won’t scale well. Prefer an event-driven approach: when you change the value of a column or row in DB that the streaming app should be aware of, also send a message asynchronously to a specific topic that will be broadcasted by your message broker.

You can then merge different DStream in a single job using DStream.join: if the first is of (K,V) and the second (K,W), the merged stream will be of (K,(V,W))

Use pooling everywhere

It’s strongly recommended to use connection pooling everywhere. It is true with database connections, and you’re probably already using it in your applications. But it’s also true with connections to other systems, like your message broker. For that purpose, a simple solution is to use Apache Commons Pool library.

Batch interval and recovery

When you design your job and calculate a relevant batch interval, you will take into account estimated messages rate, probable spikes in load, capacity of dedicated hardware, … A thing that must also be part of the reasoning is recovery in case of failure: if a driver (or any other piece of the system) fails and messages aren’t consumed for a while, they will pile up on the producer side. When application restarts, it will have to handle a massive and unusual work load. This can have several impacts, especially overwhelming systems used as data input and output providers (DB, brokers, …), and this can end up in messages lost because of processing errors.

Spark now ships back pressure mechanisms (on both sides), and you can also use spark.streaming.receiver.maxRate that will define the maximum number of records per second a batch will process. This is extremely useful in case of recovery or during application upgrade, to avoid the firehose effect of letting messages queued in a broker.

Life cycle

If you have run stateful operations, or want complete recovery of a failed driver with no data loss, checkpointing is mandatory.

Both last data received and jobs meta data are checkpointed. This means that if you modify code job and redeploy, you also need to remove checkpoint directory. Even if you modify application submission configuration (number of cores, memory to allocate, …) you’ll have to do so.

Don’t forget to enable graceful shutdown. When enabled, a hook is added to the shutdown sequence so the driver won’t stop until current batch is fully finished, while receiver has stopped and has no pending messages to be processed.

This was previously done with following piece of code

sys.ShutdownHookThread {

ssc.stop(true, true)

}

But since 1.4 you can also use the following property

spark.streaming.stopGracefullyOnShutdown=true

Tuning

Apart from obvious or mandatory parameters, there are several important things to tune up:

- configuring block interval (default is 200ms) improves performances a lot (divided batch processing time by 4 for us). Basically, for a small cluster and small amount of data, there is no need to divide incoming data into blocks of 200ms. It’s better to form bigger blocks and avoid wasting time in sending and processing small ones.

See Spark performance tuning for details. - number of concurrent jobs is also important to setup if you have more than one output operation in your driver. If you don’t raise this number, each output operation will be run sequentially. The drawback is that it will be harder to detect jobs that run longer than the configured batch time, as operations will continue to run while a new batch is getting processed.

- don’t use the default serializer: it’s a well-known fact, Java serialization isn’t efficient. Spark supports Kryo, but that requires to write read and write functions.

- configure cleaner TTL, or RDD will be kept in memory forever.

Here is a sample driver submission script

export SPARK_HOME='/root/spark'

export SPARK_MASTER='spark://host:6066'

$SPARK_HOME/bin/spark-submit \

--class com.foobot.stream.DatapointStream \

--master $SPARK_MASTER \

--deploy-mode cluster \

--supervise \

--executor-memory 1536m \

--total-executor-cores 6 \

--driver-memory 1G \

--driver-java-options "-XX:MaxPermSize=512m" \

--conf spark.streaming.blockInterval=500 \

--conf spark.streaming.concurrentJobs=6 \

--conf spark.cleaner.ttl=1800 \

--conf spark.executor.logs.rolling.strategy=time \

--conf spark.executor.logs.rolling.time.interval=daily \

--conf spark.executor.logs.rolling.maxRetainedFiles=10 \

--conf spark.streaming.receiver.maxRate=30 \

/home/ec2-user/spark-drivers/spark-driver-datapoint.jar \

$1

Conclusion

What we shared here is experience using Spark Streaming, from prototyping to production, with a particular focus on how to get the best of it without wasting too much resources.

Most of these thoughts and advice remain valid for bigger clusters and workloads, but there would be different approaches and topics to discuss.