Tuning Quartz Scheduler for large number of small jobs

What we do with Quartz Scheduler

We used Quartz Scheduler in first place to schedule time-based events on a large number of our HVAC devices, in order to trigger changes from one mode to another, and define interactions between modes. We then extended usage of Quartz to different areas, but the main usage pattern remains to run short-lived jobs that perform a single action.

The problem

Quoted from Quartz documentation: “The clustering feature works best for scaling out long-running and/or cpu-intensive jobs (distributing the work-load over multiple nodes). If you need to scale out to support thousands of short-running (e.g 1 second) jobs, consider partitioning the set of jobs by using multiple distinct schedulers (including multiple clustered schedulers for HA). The scheduler makes use of a cluster-wide lock, a pattern that degrades performance as you add more nodes (when going beyond about three nodes – depending upon your database’s capabilities, etc.).”

Indeed, it’s easy to confirm that adding nodes to a cluster doesn’t improve things at all (tested with 4, 5 and 6 nodes).

Cluster-wide lock is obtained by the QuartzSchedulerThread using a database lock (SELECT ... FOR UPDATE). It “reserves” a certain amount of triggers to execute (amount decided by org.quartz.scheduler.batchTriggerAcquisitionMaxCount), execute them (in parallel, number of worker threads can be configured using org.quartz.threadPool.threadCount, should be equal to batchTriggerAcquisitionMaxCount), then release the lock.

What happens in reality, for a clustered scheduler, is that one instance will execute the desired number of triggers while the other will be doing nothing. Clustering in Quarz is for high availability, or for load-balancing long-running jobs, but as stated in the docs, doesn’t help to run high number of short-lived jobs.

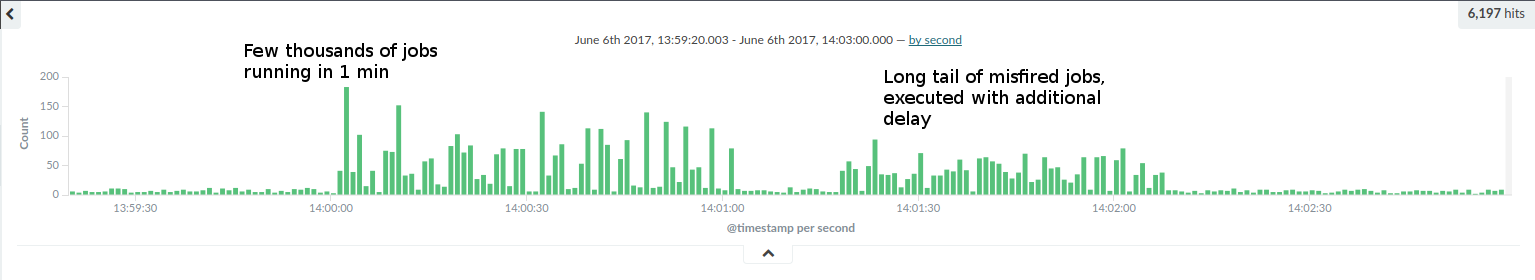

The impact for our clients was directly visible: instead of seeing desired action triggered a few seconds after desired time, it could take several minutes before kicking in. This can be illustrated by below chart:

As you can see, a large part of our end users chose to trigger events on their devices at very common times (top of hour), so we need to handle a huge burst in the number of jobs to execute at specific hours of the day.

Sharding to the rescue

Jobs sharding isn’t a feature proposed by Quartz, although database structure is ready for that. As proposed in the documentation, the idea is to spawn different scheduler instances, each one responsible for a set of shards.

Sharding can be done in different manners: creating meaningful shards (product category, company, …) or using hashing based on some key (device UUID, user ID, …). We choose the latest, as it offers best sharding capabilities (no risk to create “fat” shards) and our jobs were already stored with these IDs.

To ensure sharding will remain efficient in time, especially during re-sharding operations (adding/removing new scheduler instance), it was important to use consistent hashing: using the simple hashing approach hash(k) mod n, any change of n will require to move a large number of keys, which can degrade performance a lot during operation. Instead, it’s preferable to use a consistent hashing technique: a “ring” of virtual shards is created first and each node is responsible for a set of partitions. Adding a new node requires to move only 1/(n+1) keys to the new node (scheduler). If number of keys remain equal, time for resharding decreases when number of nodes increases.

In our case, re-sharding involves updating jobs, triggers and related definitions in DB, so the less time it takes, the better. Here is a small benchmark that illustrates time it takes to move keys (update tables) with the 2 hashing techniques:

Re-sharding after node addition benchmark (local MySQL, 8800 keys)

| nb shards | naive hashing | consistent hashing |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4400 keys moved / 360 sec | 4290 keys moved / 349 sec |

| 3 | 4800 keys moved / 460 sec | 2440 keys moved / 190 sec |

| 4 | 5500 keys moved / 570 sec | 1820 keys moved / 145 sec |

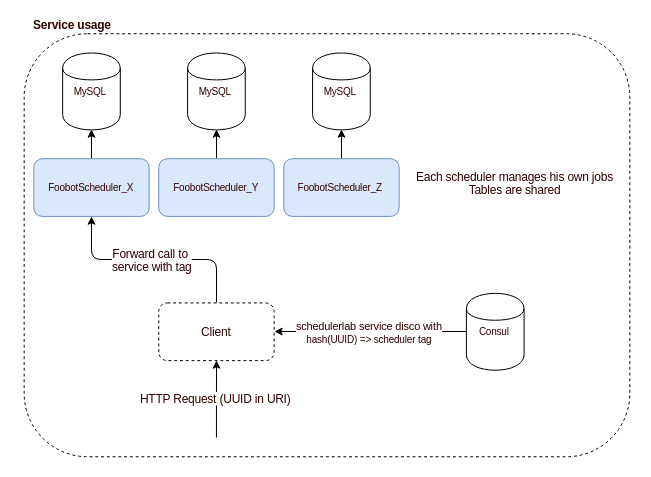

This consistent hashing mechanism has then to be made available to our scheduler API clients, so they can pick the right scheduler instance. To do that, each scheduler registers in our service discovery tool with a custom attribute (we use Consul, so the service registers with a custom tag) that represents its node ID. Then, each client discovers the service using the tag computed from hashing job key.

In above diagram we see multiple MySQL databases, which is a possible solution for further increasing throughput (although not tested). On our side, we still use the same table structures to store all schedulers data.

Benchmarking

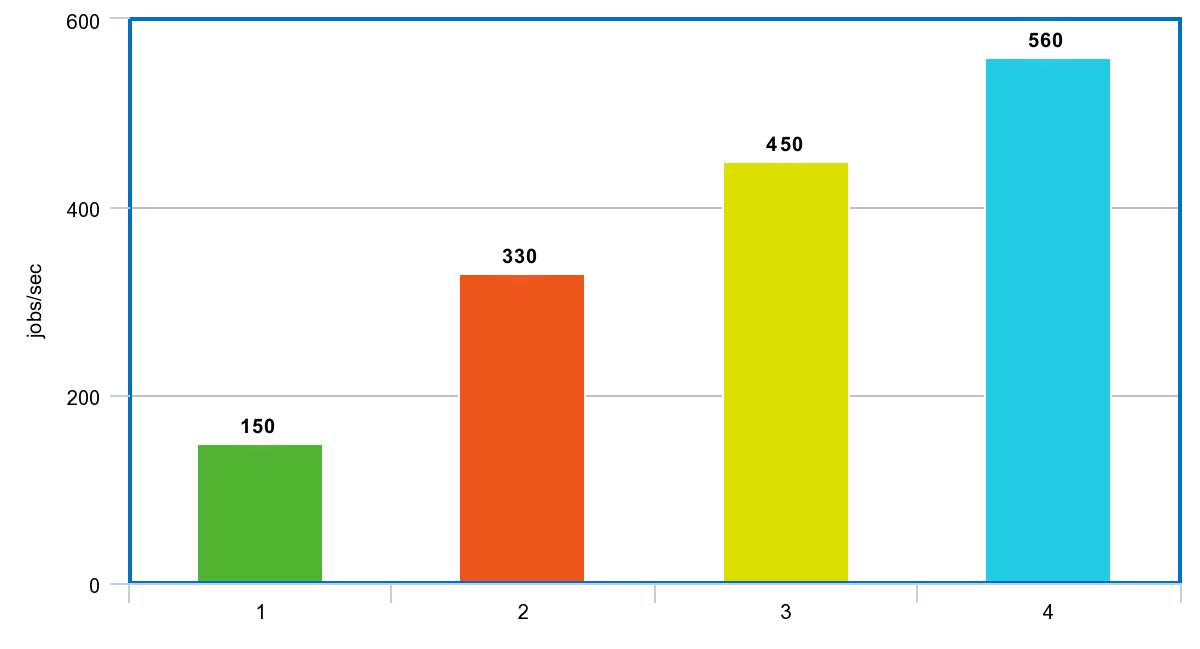

Here we’re presenting results from up to 4 schedulers: with more, we faced bottlenecks in downstream processes (benchmarks were done with “real-life” jobs), and we hit the limits of the instance we were running the jobs on (> 90% CPU usage). With 8 schedulers, and if all downstream communications are disabled, we reached 1350 jobs/sec.

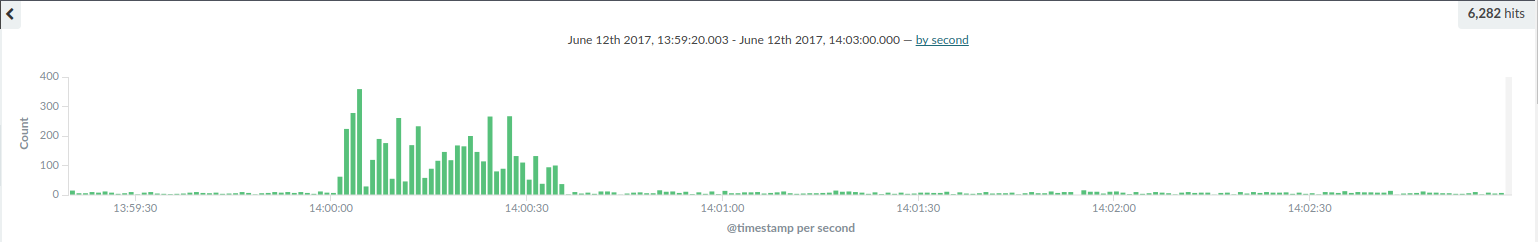

Deploying in production

We deployed 3 distinct scheduler instances in our target datacenter. Deployment took the scheduler API down for 4 minutes while resharding operation was in progress. The operation is triggered automatically by the service, if it’s configured with a node ID that has no associated job in database. Adding a new scheduler is automatic and doesn’t require any additional configuration.

Jobs at this hour now execute within an acceptable time, and most importantly we are confident we can now handle much more and keep execution times low.